A growing interest in small-scale agriculture is beginning to reverse a decades-long flight from the farm.

For nearly 70 years, the number of US farms has been declining, while the average age of farmers has been rising — it’s now 57 years old — according to the most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture survey.

A University of Vermont project found that about 70 percent of the nation’s private farm and ranchland will change hands over the next 20 years, and up to 25 percent of farmers and ranchers will retire.

“Generation after generation of farmers were making less and less money, and were not encouraging their children to farm,” says Lindsey Lusher Shute, a young vegetable famer in Tivoli, N.Y., who is a board member with the National Young Farmers Coalition.

“The number of young farmers has steadily decreased,” says Shute. “There were 6 million American farmers in 1910. In the 2007 USDA agriculture census, there are 2 million, and 119,000 of them are under the age of 36.”

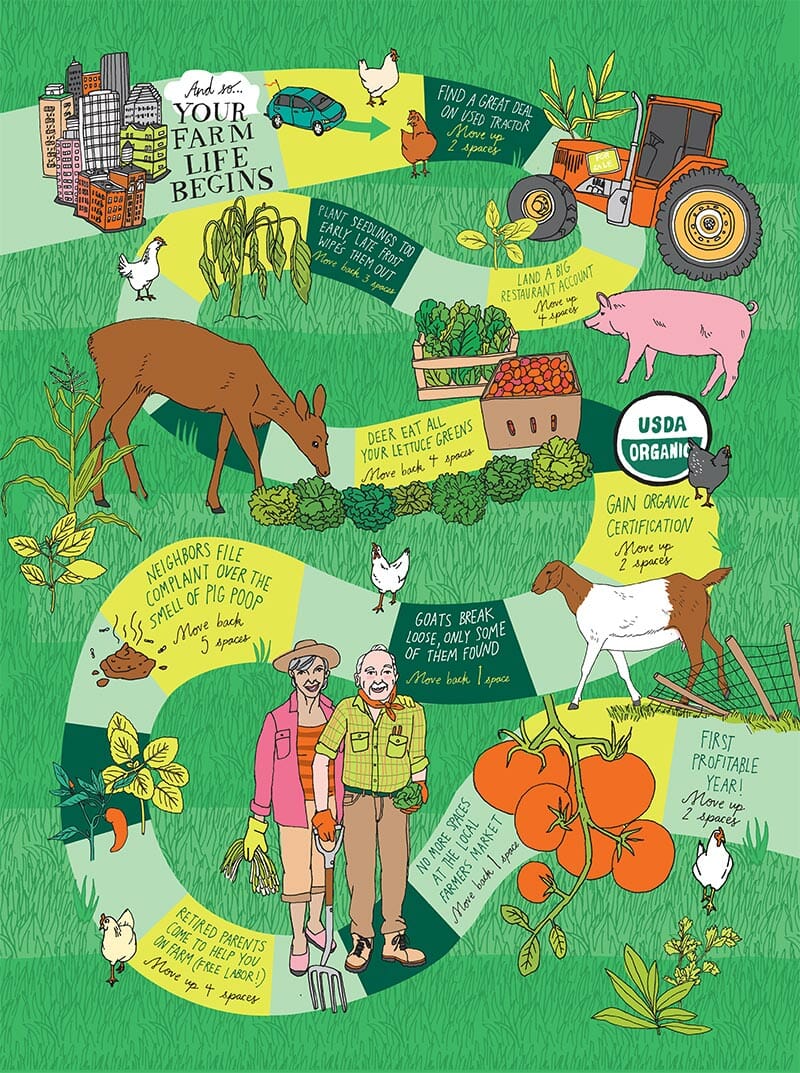

But new interest in organic farming, farmers markets and restaurants purchasing directly from farmers is turning that trend around, says Shute. “Family farms, through more local purchasing, are able to make a profit and a living. Young people are seeing this as a very rewarding lifestyle and career. For the first time in a long time, young people are interested, after decades of farming not being a very desirable career.

Farmers growing super high-volume vegetables can do quite well on one-acre plots, she said.

The most recent USDA agriculture census backs up some of Shute’s assertions. From 2002 to 2007, the number of farms increased 4 percent, and the new farmers are younger, with an average age of 48. And in one big way, their farms are very different: They’re half the size of the past. Farms founded since 2003 are an average of 201 acres, compared to the overall farm average of 418 acres.

“It’s like the craft brewing industry, where once there were only three big brewers in the country,” says Dawn Thilmany, an agricultural economics professor at Colorado State University, who received one of the new Beginning Farmer grants. “People all over started these hole-in-the-wall breweries that built up into regional forces. It’s the same model. Microfarms are like microbreweries.”

Consumers tired of tasteless tomatoes and wary of mad cow or e.coli scares have shown a willingness to spend more for healthier organic fare, at farmers markets and natural grocery chains like Whole Foods Market and Trader Joe’s. Many restaurants are boasting more localized food sources. And a new influx of young farmers are disillusioned by a dour urban economy and eager for a lifestyle that promises a measure of independence and, at least for now, a good living.

Fuelling that trend is Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack’s 2010 clarion call for 100,000 new farmers — and loan programs that start to put money where his mouth is.

Last October, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced recipients of $18 million in 2010 Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program grants.

“These beginning farmer project awards are an important first step toward realizing [Vilsack’s] goal,” says Ferd Hoefner, policy director for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. “Beginning farmers face a range of challenges to successful start up including access to credit, access to land, access to markets and technical assistance.”

Thilmany says CSU partnered with land-grant universities in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, New Mexico and Nevada to secure a $750,000 grant to offer short courses for people who want to get into farming.

“It’s the best-received extension program we’ve put on in 20 years,” Thilmany said. “We help them develop business plans and do followup mentoring, placing them with established farmers. It used to be families passing on information generationally. Now people with non-agricultural backgrounds can benefit.”

She is seeing more people in their 40s enroll in classes, many without agricultural backgrounds, “entering farming as a second career, after an early retirement or a layoff.”

People who own or lease less than 10 acres are earning $20,000 their first year and up to $300,000 within a few years, says Thilmany. “It’s a good option in urban corridors, with very high-volume crops that are grown direct-to-chef or to farmers markets. It’s a model no one saw coming 20 years ago.”

Small family farms — those with annual sales of less than $250,000 — made up 88 percent of U.S. farms in 2007. They also controlled 63 percent of the land owned, but produced only 16 percent of annual agricultural output. According to the USDA, most small-farm households typically do not rely primarily on the farm for their livelihood, and get substantial off-farm income from wage-and-salary jobs or self-employment.

But things are getting better. This year, income for U.S. farmers probably will jump 20 percent to a record, as increased crop exports and livestock sales boost food prices, the USDA said in a February issued report.

Practical Farmers of Iowa received a new USDA grant, and director Teresa Opheim reports more than 300 beginning farmers are enrolled in their network. “It’s growing all the time,” she said.

Another grant recipient, the Land Stewardship Project in Lewiston, Minn., is using the money to fund its existing programs for beginning farmers. “We’ve got a waiting list and, after 14 years of Farm Beginnings, we continue to see increased demand,” says LSP director Amy Bacigalupo. “People want to farm.” she said.

A few years ago, Neysa King was in a history PhD program at Northeastern University in Boston, studying genocide in the 20th century. Her husband Travis was working for an environmental nonprofit.

“I became disillusioned with my field,” she says. “At the same time, I became interested in food and the questionable effects of industrial agriculture on our health and environment.”

In May 2009, they left Boston for an internship on a three-acre organic farm near Brewster, N.Y.

“We had no background in agriculture,” says King. “We were simply two kids who grew up in the suburbs and went to college. Farming seemed like the intersection of everything important to us — health, sustainability, financial independence, environmental responsibility, and community.”

After a season of farming in New York, the couple moved to Austin, Texas, where they can farm year-round. They live in an apartment in town and work on two farms 10 minutes away. They also farm their own land, a third of an acre they hope to expand next year.

“We’ve fallen in with a group of about a dozen folks who came into farming from college,” King says. “The niche we’ve found is direct wholesale to local restaurants. There’s a lot of demand for chard, carrots, spinach, squash and beets. We’re not making a living yet off of our land, but with our jobs as farm workers, we’re getting by.”

Like many beginning farmers, King had romantic ideas about getting in touch with nature.

“Mine were crushed immediately,” she says. “It’s a lot of organization, business sense and science. Getting stuff to grow – on a scale that’s economic – is hard work.”